Audio programming 101

Recently, I've been working on a synthesizer (the kind that makes sounds) in Rust. I am hoping to write a large number of little articles about the things I learn as I work on this project.

To start off this series, here's a short article about audio programming.

Digital audio

To generate audio, audio software sends some digital audio signals to the audio card. Digital audio signals are just lists of floating point (decimal) numbers. Think of these numbers as "sound pressure" over time (see this page for more)

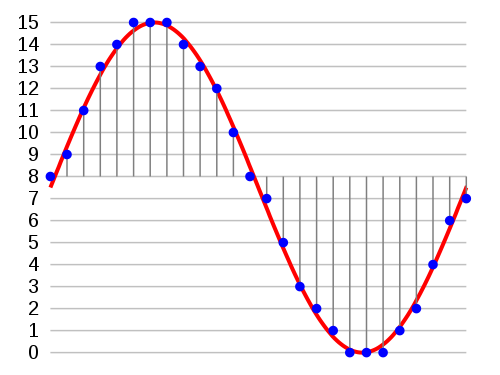

Because sound is continuous, we can't record every possible value. Instead, we take measurements of the sound pressure values at some evenly spaced interval. For CD quality audio, we take 44100 samples per second, or, one sample every 23ish microseconds. We might sample a sine wave like this (from Wikipedia):

The audio card turns these lists of samples into some "real-world" audio, which is then played through the speakers.

Types of audio software

Next let's think about a few different kinds of audio software (this list is by no means complete):

- Media players (your browser, whatever you listen to music with, a game, etc)

- Software instruments (think of a virtual piano)

- Audio plugins (an equalizer in a music player, effects like distortion and compression)

- Software audio systems

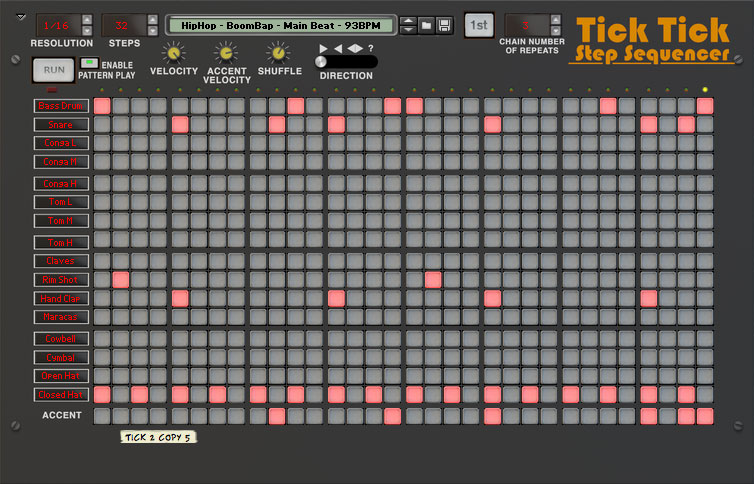

Media players are pretty self explanatory, but the others might need some explanation. Next on the list is "Software instruments." These are just pieces of software that can be used to generate sounds. They are played with external keyboards, or "programmed" with cool user interfaces.

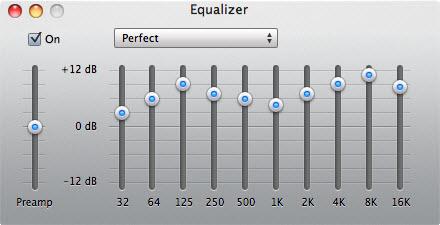

Next up are audio plugins. These are pieces of software which take audio as input, transform it in some way, then output the transformed audio. For example, a graphical equalizer can adjust the volume of different frequency ranges (make the bass louder, make the treble quieter):

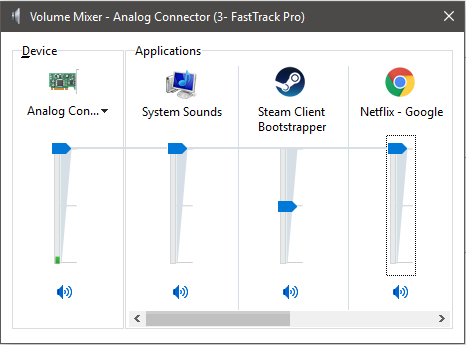

Finally, we come to what I'm calling a software audio system. Because there is only one sound card on your system, any audio you are playing on your computer must be mixed together, then sent to the audio card. On windows, using the default audio system, I can mix audio with this little mixer thing:

Some audio systems may also be able to send audio between applications, send MIDI signals, keep audio applications in sync, and perform many other tasks.

The software audio system provides a library which application developers use to develop audio applications.

Software audio systems

Most software audio systems (as far as I know) tend to work the same way. There is a realtime thread that generates samples and a bunch of other threads that deal with everything else. The audio thread is usually set up by the audio system's library. The library calls a user provided callback function to get the samples it needs to deliver to the audio card.

How fast is realtime?

In the previous section, I claimed that, at 44.1 kHz (the standard CD sample rate), we need to take one audio sample approximately every 23 microseconds. 23 microseconds seems pretty quick, but 192 kHz, a sample must be taken about every 5 microseconds (192 kHz is becoming a bit of an industry standard)!

At these speeds, it would not be possible for the audio system to call our callback function to get every individual sample. Instead, the audio library system ask us for larger batches of samples. If we simplify the real world a bit, we can approximate how often our callback function will be called. Here's a table comparing batch size to the time between callback function calls (all times in milliseconds):

| Batch Size | Time between calls @ 44.1 kHz (millis) | Time between calls @ 192 kHz (millis) |

|---|---|---|

| 64 | 1.45 | 0.33 |

| 128 | 2.90 | 0.67 |

| 256 | 5.80 | 1.33 |

| 512 | 11.61 | 2.67 |

| 1024 | 23.22 | 5.33 |

| 2048 | 46.44 | 10.67 |

| 4096 | 92.88 | 21.33 |

There are many complicated trade offs between sample rate/and batch size, so I don't want to get into them now. You can read this for a bit more information. Long story short, use the smallest batch size your computer can handle.

As audio application developers, we should make sure that our code runs as quickly as possible no matter what the batch size is. The time we spend is time other audio applications cannot use. Even if we theoretically have 5 milliseconds to run, using the entire 5 milliseconds can slow everyone else down.

Time keeps on ticking

If our callback function fails to generate samples quickly enough (or uses up all of the CPU time), the audio system will produce crackles, pops, and bad sounds. We call these buffer underruns (or xruns). Avoiding buffer underruns must be our top priority!

Everything we do in our callback function must always complete quickly and in a very predictable amount of time. Unfortunately, this constraint eliminates many things we often take for granted, including:

- Synchronization with locks

- Blocking operations

- Operations with high worst case runtime

- Memory allocation with standard allocators

First, we can't use locks or semaphores or conditional variables or any of those kinds of things inside of our realtime callback function. If one of our other threads is holding the lock, it might not let go soon enough for us to generate our samples on time! If you try to make sure you locks will always be released quickly, the scheduler might step in and ruin your plans (this is called Priority Inversion). There are some cases in which it might be okay to use locks, but, in general, it is a good idea to avoid them.

Second, we cannot perform blocking operations in the realtime callback function. Things that might block include access to the network, access to a disk, and other system calls which might block while performing a task. In general, if I/O needs to be performed, it is best to perform the I/O on another thread and communicate the results to the realtime thread. There are some interesting subtleties to this, for example, can the following code perform I/O?

int callback(/* args */) {

float* samples = // get a contiguous array of samples in a nonblocking way

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; i++) {

output_sample( samples[i] );

}

}

Unfortunately, it can. If the array of samples is extremely large, the samples might not all actually be in physical memory. When the operating system must contend with increasing memory pressure, it may move some of the virtual memory pages it manages out of physical memory. If the page isn't in main memory, the operating system has to go get it from somewhere. These pages are often moved to a hard disk, so getting them will require blocking I/O.

Luckily, this sort of thing is only an issue if your program uses

extremely large amounts of memory. Audio applications usually do not

have high memory requirements, but, if yours does, you operating system

may provide you with a workaround. On linux, we can use the system call

mlockall to make sure certain pages never leave physical memory:

mlock(), mlock2(), and mlockall() lock part or all of the calling process's virtual address space into RAM, preventing that memory from being paged to the swap area.

Next, we want to avoid operations which have a high worst case runtime. This can be tricky because some things with bad worst case runtime things have a reasonable amortized runtime. The canonical example of this is a dynamic array. A dynamic array can be inserted into very quickly most of the time, but every so often it must reallocate itself and copy all of its data somewhere else. For a large array, this expensive copy might cause us to miss our deadline every once and a while. Fortunately, for some data structures, we can push these worst case costs around and make the operations realtime safe (see Incremental resizing).

Finally, memory allocation with standard library allocators can cause problems. Memory allocators are usually thread safe, which usually means that the are locking something. Additionally, allocation algorithms rarely make any time guarantees; the algorithms they use can have very poor worst case runtimes. Standard library allocators break both of our other rules! Luckily, we can still perform dynamic memory allocation if we use specially designed allocators or pool allocators which do not violate our realtime constraints.

What do we do?

In general, there are a few cool tricks we can use to design around these problems, but I'm not going to discuss any of them in this post. Future posts will discuss possible solutions and many of their tradeoffs, eventually.

If you can't wait, here are some interesting things you can read to learn more:

- Overview of Design Patterns for Real-Time Computer Music Systems

- SuperCollider implementation details from the SuperCollider book

- Supernova for SuperCollider a Masters thesis discussing some of these issues

- this excellent blog post

See you next time!