Ants

For my CS242 final project, I simulated ants with Erlang.

In the following video we have a 1000 by 1000 grid with 2000 ants running around on it. There is food in a small square on the upper left. The simulation ran for 1 hour (53,840,103 events were recorded).

Model

I've attempted to capture two behaviors of real ants with my simulation: ants communicate using pheromones (scents), and they want to find food.

Pheromones are a way for an ant to communicate the location of food to other ants. Each cell in the simulation has a pheromone strength associated with it. When an ant moves, it uses the pheromone strength of the cells around it to compute the probability that it will move in that direction.

Additionally, my ants have multiple movement modes.1 They can be in "away from home" mode or "towards home" mode. When an ant starts moving, it favors moving away from its starting cell. When it finds food, it switches modes and favors moving towards its starting cell. If it ever reaches the starting cell, it switches modes again and goes to find more food. I believe that real ants also use pheromones to find their way back home (instead of magically remembering the absolute coordinates of their homes), but I used this method to simplify the model while still sort of capturing the return to home behavior.

There is a mechanism to change the relative importance of distance and pheromone strength. When an ant finds food, it ignores pheromones until it gets back home.

Food can be placed on any cell in the simulation. Nothing actually tracks how much food gets carried home, and the supply of food at a given cell does not change when an ant discovers food. If I were to continue the project, it would be really interesting to see how much food actually gets "home" and to include a changing food supply in the model.

Pheromone Propagation

When an ant is at a given cell, it gets the max pheromone strength of its neighbors. It then checks if the strength of the its current cell is greater than the max strength of its neighboring cells. If its current cell has a lower pheromone value than the max of its neighbors, the ant updates the strength of the current cell to half of the max strength of its neighbors.

When ants find food, they set the pheromone strength of the cell the food was on to a high value, then they start moving back home. This should, in theory, cause the pheromone trail to follow them. This doesn't work as well as I had hoped because the pheromone trail drops off too quickly, but, it is easy to implement, so I stuck with it.

The Erlang Stuff

If you aren't familiar with Erlang, here is a super quick overview of the concurrency construct in the language.

Actors (processes in Erlang terminology) run concurrently and send messages to each other. These messages are asynchronous, so if actor A sends a message to actor B, it doesn't wait for B to respond to proceed with it's next instruction. A message can also contain any sort of data you care to send.

An ant actor and a grid cell actor form the core of my simulation.

Cells know who their neighbors are, their pheromone strength, if they have food on them, and which ant occupies the cell (can be undefined). Only one ant can occupy a given cell at any moment in time.

A cell knows how to handle the following messages (and a few others):

who_are_your_neighbors- asks the cell to send a message to someone with its neighborsmove_me_to_you- tells the cell to set its current occupant to the ant sending the messageive_left- tells the cell that the ant sending the message has left the cell

Ants know what cell they are on, what direction they are going, where they started, and a few other less important things.

Ants know how to handle these messages (and a few others):

wakeup_and_move- tells the ant to try to move somewhereneighbors- a message sent to an ant by a cell when the cell reports who its neighbors aremove_to- tells an ant to change its current cell to some other cellmove_failed- tells an ant that its move failed

Simulation

When the simulator starts, it loads a config file specifying things like the size of the grid and the location of food, builds the grid of cells, puts ants on the upper edge of the board, then starts a wakeup_and_move_loop for each ant.

These loops tell their respective ants to wake up and perform their move over and over again until the simulation is shut down.

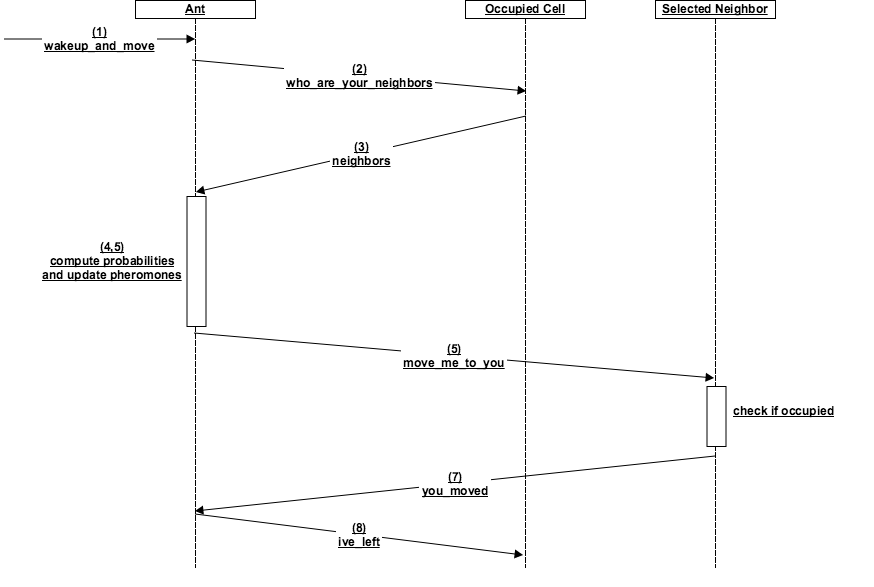

Wakeup_and_move

When an ant receives a wakeup_and_move message, it has to figure where it wants to move, if it can move there, and it needs to perform the pheromone propagation step. I don't want to let two ants occupy the same cell at once, but it isn't so bad if one ant is sort of in two places at once (I think). Those rules motivate the following sequence of messages for an ant move:

- The ant receives a

wakeup_and_movemessage - The ant sends a

who_are_your_neighborsmessage to its current cell - The current cell receives the

who_are_your_neighborsmessage and sends the ant aneighborsmessage with the list of its neighboring cells - The ant decides which of these neighbors to move to using probabilities explained earlier

- The ant performs the pheromone propagation step

- The ant sends a

move_me_to_youmessage to its selected cell - The selected cell checks if it is currently occupied

- If it isn't occupied, it sets its current occupant to the ant trying to move and sends a you_moved message back to the ant

- If it is occupied, it sends a move_failed message back to the ant

- The ant receives either a

move_failedor ayou_movedmessage- If the ant received a

you_movedmessage, it sends anive_leftmessage to its current cell, updates its current cell to the selected cell, then goes back to sleep - If the ant receives a move_failed message, it does nothing and goes back to sleep

- If the ant received a

If you look carefully, you might notice that, between steps 7 and 8, two cells think they are occupied by the same ant. This prevents collisions but introduces this strange "ant in flux" state. I would rather accept the double occupancy issue than the collision issue.

Data

As the simulation runs, the ants are generating all sorts of data that should probably be recorded somewhere. This is a bit of a challenge because there is no single entity that knows the state of the entire system at any given time, so you can't just record a sample of the state of the simulation somewhere every once in a while.

So, I decided that ants should be responsible for reporting their own movements and should report the pheromone strength changes they make. For a couple of reasons that don't totally make sense, I decided to create one file per ant, and have the ants log timestamped (wall clock time) events to those files. So, for a 2000 ant simulation, I end up with 2000 ant-event files on disk somewhere.

There are all sorts of things wrong with the one file per ant approach.

The biggest is speed. Having one file per ant means I have to merge all of these ant-event files before making a visualization. These files can get large so this is a slow process (and memory intensive if you write your script poorly (oops)).

Other than speed, one file per ant puts an upper limit on the number of ants I can simulate at a time because I can't open an unlimited number of files on any sort of machine. I won't even mention the strange I/O behavior.

Fortunately, computers are fast, events are small, and I have a decent amount of memory in my laptop, so this technique was "fast enough" given the scope of the project.

Making the Video

Ants are moving all the time in an uncoordinated manner, moving a lot, and sometimes moving at exactly the same time so there isn't a totally obvious way to decide when to draw a video frame. I took 100 miliseconds worth of simulation data (timestamps are in real earth time) and used the last position of every ant in that time slice to make a frame.

MoviePy makes the rest really easy. All I have to do is build a frame by populating a numpy array, and throw that array at MoviePy. MoviePy treats that like an array of pixels and spits out a video that plays some number of frames per second.

Conclusions

The naive model of any movement I used almost works. If I were to improve the pheromone propagation mechanism and add changing food supplies, I suspect the behavior would become a bit more interesting. Another next step would be the addition of some obstacles on the grid so that the "always favor moving away" approach would fail, necessitating a more intricate "looking for food" mechanism.

Erlang is an interesting language and I'm glad I had an opportunity to fiddle with it, but some of its peculiarities can be annoying. First of all, the lack of static typing is a pain (I know about dialyzer). It is also difficult to do things like prioritize certain messages over others (if I want to shut down the simulation, I want my stop message to take precedence over anything else), and badly behaving actors can create strange situations. For example, it is possible that some misbehaving actor can fly in and start sending wakeup_and_move messages to ants while they are executing the 8 step move and confuse the ant, the cell the ant is trying to move to, and the cell the ant is currently on. Despite its oddities, the language and the VM are super cool and I would use them again when appropriate.

Unfortunately, I would not say that this project was particularly appropriate for Erlang. The actor model was an interesting way to think about ants and cells, but the problem doesn't quite fit Erlang's strengths as a fault-tolerant language for distributed systems. There is a possibility that the distributed nature of Erlang might enable some interesting simulation sort of things, but there is little reason to take advantage of the fault tolerance in a project like this. Additionally, there are others ways to implement a simulation like this which mitigate many of the issues I encountered along the way (but might introduce other ones).

Overall, this was a fun project and I'm glad to have gotten to work on it.

The buggy, messy code is on github.

Footnotes:

I like my ants like I like my editors.